I was going to do another regional/geographic post–The Hill Country next, I think–but I decided I ought to go ahead and finish up talking about Texas Government and get it over with. Schools will go into another post all together, but I’ll talk about county government here and the government that the average person will bump up against.

|

| Hill County Courthouse, Hillsboro, built 1890 |

Texas is rightly famous for its courthouses. There are 254 counties in Texas. Most of them are about 1000 square miles, though some, like Rockwall and Somervell Counties, are extra small, and others, like Brewster and Pecos Counties in the Big Bend, are extra large. Most of the courthouses were built in the late 1800s as a beacon for local pride.

I am going to include the courthouses for the various counties I have lived in–most of them anyway. The Galveston County Courthouse is probably the most modern of them, and I’m going to say that’s because of the hurricanes that come through here on a regular basis. Galveston has always been the county seat and since it’s on a barrier island in the Gulf of Mexico, it’s not a question of IF a hurricane is coming through. It’s a question of WHEN. Anyway, this first courthouse pictured is the one where I worked for a number of years. I only got to work in the actual courthouse about a year–10 months at the beginning and about 2 months at the end of my work time here. It caught fire on January 1, 1992, and for the next several years, we worked in our chicken wire and plywood annex a block away.

|

| Hill County Courthouse, Jan. 1, 1992 |

When I started, I worked in an office carved out of the district courtroom on the second floor just across from the windows above the door in the non-fire picture. After the restoration, the district courtroom was put back into its original condition, and the county attorney’s office was moved to the third floor on the south east corner (the left side of the visible face in the picture), just under the mini-tower on the corner.

Counties in Texas are governed by the commissioner’s court which is presided over by the county judge. This is an administrative, executive position, NOT a judicial position. Originally, it was both, but in most counties, they have created County Courts at Law which have taken over all the judicial tasks.

When I worked at the courthouse, back in the ’90s (we moved to the Panhandle and Donley County in 1999), the county judge still handled the judicial responsibilities because the Texas Constitution had a Hill County-specific constitutional amendment placing the county court under the supervision of the district court. Now, there is a county court at law in Hill County and an old friendly acquaintance of mine is the judge. (I’m tickled pink about it. He’s a good guy. I’m sure he’s an excellent judge.) However, there are still some rural counties where the county judge handles the judicial responsibilities.

|

| Donley County Courthouse, Clarendon, built 1890 |

The commissioner’s court is the legislative body of the county and they are in charge of the county’s budget. Even though all those other people–from the sheriff to the tax assessor-collector–are elected, the commissioner’s court is in charge of how much money they get. This can make things awkward when the officials get crosswise with each other. I remember one instance when the sheriff in Tarrant County (Fort Worth) was doing some things the commissioners didn’t like–buying helicopters and other “crazy” things–and they tried to bring him to heel by cutting off his funds. Didn’t work too well.

There are four commissioners in each county. Besides being in charge of setting the county’s budget and passing local ordinances (very few) and approving residential plats (very few bother to ask for approval), the commissioners are in charge of the construction and maintenance of the roads and bridges in their precinct. (They even put up pictures of it on the county website…) This is why county commissioners are often called Road Commissioners. The names are pretty much interchangeable, especially in the rural counties. Tommy Joe Davis, who was tax assessor-collector when I lived in Hill County, used to joke that the best way to get new computers for the courthouse offices was to paint them yellow and stick a grading blade on the front. It can sometimes be hard to get road commissioners to approve funds for anything but road repair equipment.

|

| McLennan County Courthouse, in Waco, built 1901 |

Yes, it can be confusing to have the CEO of the county called the county judge, and the judges of the county courts at law (which are primarily criminal courts handling misdemeanors, but can also handle some minor civil matters) all called county judges. But only one is The County Judge. And he’s the only one who isn’t an actual judge in a court of law.

(I lived in McLennan County while I was attending Baylor University, which is in Waco, and we lived there the first year the fella and I were married, while he was finishing up his Master’s.)

By the state constitution, each of the 254 counties has four justices of the peace and four constables. Texas JPs have constitutionally been the ones to pronounce cause of death, and at least one of them is famous for having declared the cause of death to be “lead poisoning” because the dead man got shot full of lead bullets. These days, they do not have to be lawyers, but they do have to attend quite a bit of training. In most places they no longer have to go out to deaths, unless it’s a very rural county, but they still have to sign the paperwork. They also preside over courts handling traffic tickets in the rural areas, and like all the other judges, they can marry people. (The district court judge in Hill County–a good friend and second cousin once removed of the fella’s–performed the wedding of our older son.) (District judges can also waive the three-day waiting period of the marriage license, if you need that in your story.)

|

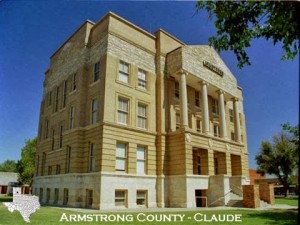

| Armstrong County Courthouse, built 1912 |

At the moment, Galveston County has nine (9) justices of the peace, and I think, 9 constables to go with them. (The constitution allows the county to create more, but each county has to have at least four.) The current commissioner’s court is trying to reduce that back to the constitutional four to save money, and of course, the JPs are fighting them because they don’t want to lose their jobs. It’s a big political mess, and quite the fight.

(I never lived in Armstrong County, but I drove through Claude once a week, right by the courthouse, on my way into Amarillo, when we lived up that way. It has one of the more modern-looking courthouses… The city-county library is in the basement…)

Constables provide security for the JP courts, and spend most of the rest of their time on the job as process servers. This saves the sheriff money and time having his/her personnel doing the job. We have to have constables anyway, so they may as well take some of the work from the sheriff’s office. But they don’t always. Only if the sheriff wants to give the work away. And remember, all these people are elected. Every single one of them.

|

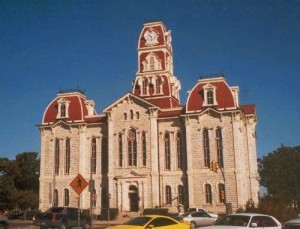

| Parker County Courthouse, Weatherford, 1894 |

I’ve mentioned the tax assessor-collector a number of times. This is another elected office, and one of the few constitutionally mandated county-wide elected offices. (District judges and district clerks are elected, but sometimes they’re for more than one county, and sometimes, there’s more than one in a county.) The tax assessor-collector collects taxes for the county but can also collect them for other governmental entities. School districts, community college districts, MUDs, even smaller cities can and often do contract with the tax assessor-collector. They are the ones who handle car registrations (license plates) and car titles. The tax assessor-collector office even issues the beer and wine sales permits.

(I never lived in Parker County, but doesn’t the courthouse look like the one in Hillsboro? Except the roofs are colored! And it’s only two stories… Or looks like it.)

Every county in Texas has a sheriff. But the sheriff in an urban county has somewhat different responsibilities than one in a rural county–or, rather, he is charged with the same responsibilities: maintaining and operating the county jail and policing the unincorporated areas of the county. But those duties play out differently in rural and urban areas.

|

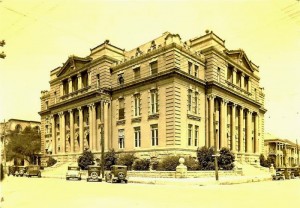

| Galveston County Courthouse, Galveston, 1966 |

Most urban counties, especially the ones with the “big six” cities, don’t have a lot of unincorporated land. The city–or cities, because most of them have suburbs in the county with the city–fill it all up. Tarrant County has Fort Worth, but it also has Arlington, Hurst, Euless, Bedford, North Richland Hills, Saginaw–and probably more, but I’m not sure if they’re all in Tarrant County. Same with Dallas. Dallas County also has Irving, Grand Prairie, Richardson, Plano, Mesquite, etc., etc. But not much territory that’s not inside the limits of all those cities. Harris County, where Houston is, has more unincorporated land than most large-city counties, because it’s a large county. But still, it doesn’t have nearly as much as Brewster County. Or even Briscoe County. Because those are rural counties.

(The 1899 Galveston County Courthouse was across the street from this one, but it was torn down in 1966. It’s entirely possible that the old one was damaged badly in Hurricane Carla in 1961, but I can’t find any confirmation of that. This one was finished only five years after Carla, which is really soon, given how slowly things move in government, especially after hurricanes. There are no courts of law in this courthouse. The federal court is in the post office/federal building down on 25th Street, and the state and county courts are in the new justice complex right at the entrance to the island on Broadway.)

|

| Old Galveston County Courthouse, 1899, demolished 1966 |

What those large counties do have is lots of criminals. They need big jails. So urban sheriffs spend most of their time managing the county jail. The county jail is required to hold the people the cities arrest until they make bail or go to court. Most cities have fairly small jails, because they’re expensive and because they only have to hold arrestees long enough to cart them over to the county jail. This is why the Tarrant County commissioners got so peeved with their sheriff, because he was buying helicopters to police the unincorporated parts of the county, and Tarrant doesn’t have much in the way of unincorporated parts. The commissioners thought he should spend more money on the jail. Remember, the sheriff is an elected position. He has to run for office every four years. Used to be every two, but now it’s four. The sheriff runs when the governor runs, which is in the even-numbered year between presidential elections.

|

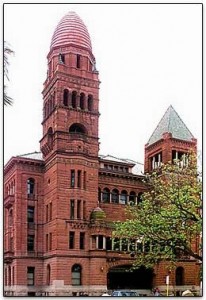

| Bexar County Courthouse, San Antonio, 1896 |

Even in rural counties, the way the sheriff does things can be different. In Hill County, which was and is a rural county, there were four fair-sized cities: Hillsboro, Whitney, Itasca and Hubbard. (There are also the micro-cities of Aquilla, Brandon, Blum and maybe one other, but those cities are really small and don’t have their own police.) Hillsboro had a population of just over 5,000 when we lived there, now it’s about 8,500. The other cities are smaller. But they all had their own police departments. Hillsboro had about 10 or 15 officers, and even had a two-man detective bureau. Whitney had 3 to 5 officers, Itasca and Hubbard each had two. The sheriff backed them all up, and policed everything else. The sheriff had more deputies than any of the police departments. When that boy was running from the police in his cotton stripper, he was running from the sheriff’s deputies.

(I included the Bexar County Courthouse because it has such a distinctive look. Plus my dad lived in San Antonio. But really, what other government building has such a phallic looking red tower???)

When we moved to Donley County, the largest town in the county, Clarendon, had a population of just under 2,000. Howardwick, the town out by Greenbelt Lake, had a population of 300 or so, and Hedley is about the same size. And the sheriff policed it all. Clarendon didn’t want to have to hire police officers. They helped pay for the sheriff’s office, but the sheriff handled everything. And the jail was on a corner of the courthouse square. Thing is, because the county is so rural–all those cows don’t commit much crime–and it’s not on the Mexican border, so the sheriff and his not-very-many deputies could handle pretty much everything. There were some highway patrolmen who lived in town, too. The road from Dallas to the skiing mountains in Colorado runs through Donley County, so people had/have a bad tendency to speed. Clarendon only had one stop light. Did they really have to run it?

|

| Wise County Courthouse, Decatur, 1896 |

One more thing. I had a friend who wanted to write a book where the hero’s and the heroine’s relatives were running for the same local office–county commissioner or something–so that the politics would amp up both the humor and the conflict in the story. And her editor (from New York City) thought they should be running for the Senate (The U.S. Senate, not the state senate), because local politics just wouldn’t be important enough to create much conflict. And that’s just wrong.

(Never lived in Wise County either, but drove through Decatur a lot of times. It’s on the same highway Clarendon is, just a lot closer to Fort Worth. And I like their courthouse.)

First off, a person running for senator in Texas would be running a statewide race. And Texas is a really wide state. Remember, it’s almost 1000 miles from top to bottom, side to side. They would be spending most of their time running from one side of the state to the other, from one of the Big Six cities to the other. They wouldn’t have time to get personal. It’s not a personal race. And that’s the thing about local politics. It’s personal.

People tend to get a whole lot more “het up” about local races than they do about political races where they don’t have to deal with the elected official every day. When the winner goes way off somewhere, like Austin, or even Washington, D.C. Maybe those larger races carry more clout in the larger world. But they’re not important. They’re not personal. It’s not Butch from down the street trying to cut out John from church in that respected role. Or even Aunt Myrtie. Local elections can create a whole lot more conflict than any statewide or even national election any day. Especially in a small town in a rural county.

What else might you want to know?

|

| Montague County Courthouse, Montague, 1912 |

Oh. A couple of “pronounciation” things: Montague County. It’s not pronounced “MON-ta-Gue” (rhyming with glue or Gru from Despicable Me), it’s pronounced “Mon-Tayg” (with a hard G at the end and both syllables getting the same emphasis). And Borger (historic oil town in the Panhandle, with a still operating oil refinery) is pronounced with a hard G. It’s not “Bor-jer.”

This is NOT a comprehensive, formal survey of local Texas government. It’s just a bunch of stuff writers might want/need to know. A jumping-off point for things to research. Hope it helps somebody…